Today marks the centenary of the sinking of the Royal Mail Ship Leinster (10am October 10th 1918), after it was struck by two torpedoes from a German U-Boat 16 miles off the Dublin coast near the Kish Lighthouse. Commemorations are taking place in Dún Laoghaire for the 501+ passengers and crew died that day, the worst maritime disaster on the Irish Sea. Many of the passengers were military who were returning from leave in Ireland.

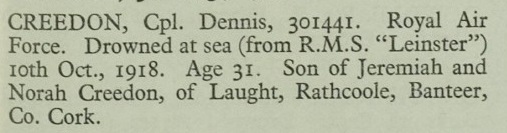

Among them was Dennis Creedon, of Laught, the son of Jeremiah and Norah Creedon, who was returning to Britain after leave at home. He was 31 years and left a wife Julia behind him. He was the last local person from Millstreet to die in World War I.

He had moved to Wales where he was working in the mines. He married Julia Moynihan in 1913, and when the war broke out, like his three brother in laws, he joined the British Army, seemingly like many others, for a better income to support his family. His time was apparently uneventful, and he was based in Bedford. He received a promotion to Corporal and transferred to the RAF on 17th September 1918 (#301441), where his trade within the army was as a “Hospital Orderly”. Having been on leave, he was returning to Britain, when he was drowned that day. His body was recovered, and was sent to Millstreet by train where it was waked in St. Patrick’s Church, and the following day buried at Kilcorney Cemetery with his family. He is also commemorated at the Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton.

====

Denis’ Family

Parents: Marriage of JEREMIAH CREEDON, Leacht and HONORA HALLORAN, Cahirdonee (Caherdowney) on 01 March 1870

Denis: Birth of Denis Creedon on 30th August 1887 to Jeremiah Creedon and Norah Creedon, formerly Hallinan, of Laught, Rathcoole, [birth registration]

1901 Census: the Creedon family were living at Laught, Rathcoole:

Jerry Creedon, aged 68, a Farmer, married, ( – 1915)

Hanorah, his wife, aged 51, a Housekeeper, (- 1945)

1. John, son, aged 25, an Agricultural Labourer, (b. 1875 – 1902??)

2. Kate, daughter, aged 15, a Scholar, (b. 1885)

3. Denis, son, aged 13, a Scholar, (b. 1887)

4. Ellen, daughter, aged 11, a Scholar, (b. 1889)

5. Con, son, aged 9, a Scholar. (1890 – 1942)

Missing from the 1901 census are:

6. Timothy (b. 1872)

7. Jeremiah (b. 1873)

8. Mary (b. 1877)

9. Margaret (b. 1879)

10. Bridget (b. 2 Jan 1881)

11. Kate (b. 05 Mar 1881) died at 10 weeks from Croup

12. Hanoria (b. 1882)

13. Julia, (b. 01 Oct 1883);

1911 Census:

1. The Creedons parents are at home, but all the children are gone (the census is filled in Gaelic … very unusual). They have two elderly visitors/boarders – Donnchada Ó’Buachalla and Brigid Ní Buachalla.

2. Siblings Julia and Con are working at Julia O’Keeffe’s shop on Main Street.

1915: Death of Jeremiah (father), aged 81 in Laught

====

Before the War

Denis had moved to Wales where he was working in the mines. It was around the time when the mines in Dromtarriffe were closing, and a number of locals moved to Wales to work in the mines there. Once established friends and family followed them. One of those was Cornelius Kelleher, who also worked in the mines. However Cornelius died in a mining accident and it surely had an effect of Denis.

He married Julia Moynihan in 1913 of Mountain Ash. She had a number of brothers who also worked in the mines, and her parent’s home was also a boarding house for miners. It’s highly likely that she met Denis through her connections with the mines.

We knew that Julia was born in Wales, but the name Moynihan was a clue that her family must have come form the Duhallow area. Sure enough Julia turned up in the 1911 census in Mountain Ash, and it showed that her parents were actually from the Millstreet area, father Denis from Rathcoole, and mother Julia was from Adrivale. They were married in 1870 in Millstreet, and the first of their children were born in Ballineen (on the road from Millstreet to Rathcoole). The family seemed to have moved to Wales in around 1882 and settled in Mountain Ash where they stayed.

After Denis died, Julia visited Denis’ family in Millstreet, and stayed for some time, but she returned and contact with he was lost over time.

====

Time in the Army

We don’t know why Denis joined the British Army on December 14th 1914. Suggestions are that it paid a better wage to support him and his wife, and that it was just seen as another job, maybe he didn’t like the mining work, maybe the death in the mines of his friend Cornelius Kelleher affected him somehow. There may have been some influence from his wife’s three brothers who had also worked in the mines, and who all signed up the Army.

What would be obvious was that it would not have been popular back home, where his parents would have been supporters of the move Independence in Ireland (Theirs is the only census form that I’ve seen ‘as Gaeilge’ in the Millstreet area).

But his time in the army was apparently uneventful, and he saw no action just work. One newspaper article (June 3rd 1916) on his brothers-in-law at home on leave says that he was working in the Army Service Corps in Bedford, where he had already been promoted to Corporal.

The Army Service Corps was an essential part of maintaining the army and keeping its soldiers fed, watered and equipped and able to fulfil their roles on the front line and the home front: providing food, equipment and ammunition, providing horses and vehicles, and keeping supplies moving by horse-drawn and motor transport, rail and water, to wherever they were required.

He received a transferred to the RAF on September 17th 1918 (#301441), where his service record recorded his trade within the army was as a “Hospital Orderly”. Soon after he was on leave at home in Lacht. On the day he was leaving Millstreet to head back to Britain, a neighbour remembered seeing him going to fetch water for his parents, in his full military gear. He headed for Dún Laoghaoire, and onto the R.M.S. Leinster, the morning of October 10th, where he and over 500 others met their fate that day.

Service Record:

Name:Denis Creedon

Gender:Male

Age on attestation:27

Birth Date:30 Aug 1887

Birth Place: Dromtarriff, Millstreet, Cork, Ireland

Religion: Roman Catholic

Current Engagement in HM Forces: Army 14/12/14

Date of entry into RAF: 17/9/18

Civilian Occupation: Miner

Marriage: to Julia Moynihan [ref]

– Date: 13/1/13

– Town: Mountain Ash, Pontypridd, Wales

– verified from marriage cert: yes

Persons to be informed of casualties: Julia Creedon, Laught, Millstreet, Co. Cork. Wife.

Description: Height: 5 ft 8 1/2 inches; Chest 36 inches; Hair: Auburn; Eyes: Blue; Complexion: fair.

Discharge: Died by Drowning RMS Leinster 10.10.18

Promotions: Transferred RAF Cpl. 17.9.18

Trade Classification: Hospital Orderly

Archive reference AIR 79/2623

[Service Record 1][Service Record 2]

The R.M.S. Leinster and the Sinking

Departure: Shortly before 9 a.m. on 10 October 1918 the R.M.S Leinster left Carlisle Pier, Kingstown (now Dun Laoghaire), Co. Dublin, Ireland. Bound for Holyhead Anglesey, Wales she carried 771 passengers and crew. The ship was commanded by Captain William Birch (61), a Dubliner who had settled with his family in Holyhead. Apart from Birch, the Leinster had a crew of 76, drawn from the ports of Kingstown (Dun Laoghaire) and Holyhead. Also on board were 22 postal sorters from Dublin Post Office, working in the ship’s onboard postal sorting room. There were 180 civilian passengers, men, women and children, most of them from Ireland and Britain.

But by far the greatest number of passengers on board the Leinster were military personnel. Many of them were going on leave or returning from leave. They came from Ireland, Britain, Canada, the United States, New Zealand and Australia. On the Western Front the German Army was being pushed back by the relentless assaults of the Allied armies. On 4 October Germany had asked U.S. President Woodrow Wilson for peace terms.

As the Leinster set sail the weather was fine, but the sea was rough following recent storms. Earlier that morning a number of Royal Navy ships at sea off Holyhead were forced to return to port due to the stormy conditions.

Torpedoed! Shortly before 10 a.m. about 16 miles from Kingstown (Dun Laoghaire) a few people on the deck of the Leinster saw a torpedo approaching the port (left) side of the ship. It missed the Leinster, passing in front of her. Soon afterwards another torpedo struck the port side where the postal sorting room was located. Postal Sorter John Higgins said that the torpedo exploded, blowing a hole in the port side. The explosion traveled across the ship, also blowing a whole in the starboard side.

In an attempt to return to port, the Leinster turned 180 degrees, until it faced the direction from which it had come. With speed reduced and slowly sinking, the ship had sustained few casualties. Lifeboats were being launched. At this point a torpedo struck the ship on the starboard (right) side, practically blowing it to pieces. The Leinster sank soon afterwards, bow first.

The cruel sea: Many of those on board were killed in the sinking. In lifeboats or clinging to rafts and flotsam, the survivors now began a grim struggle for survival in the rough sea. Many died while awaiting rescue. Eventually a number of destroyers and other ships arrived. The survivors were landed at Victoria Wharf, Kingstown (Dun Laoghaire), where the ferry terminal now stands.

Doctors, nurses, rescue workers and a fleet of 200 ambulances rushed to Victoria Wharf. Those needing medical care were brought to St. Michael’s Hospital in Kingstown (Dun Laoghaire) and several Dublin Hospitals. Those not requiring medical treatment were brought to local hotels and guest houses.

In the days that followed bodies were recovered from the sea. Funerals took place in many parts of Ireland. Some bodies were brought to Britain, Canada and the United States for burial. One hundred and forty four military casualties were buried in Grangegorman Military Cemetery in Dublin.

Officially 501 people died in the sinking, making it both the greatest ever loss of life in the Irish and the highest ever casualty rate on an Irish owned ship. Research to date has revealed the names of 529 casualties.

Reporting in the Irish Times the day after the tragedy.

The aftermath to the massive loss of life was fraught and controversial. Many facts were never established and calls for a public enquiry were refused by the British, who presumably didn’t want to exacerbate their wartime embarrassment. Censorship continued after the war.

The Evening Herald was shut down for four days merely for reporting the sinking (before the deaths were even known about) without censor approval. The press censor prevented any information being published that there were soldiers on board.

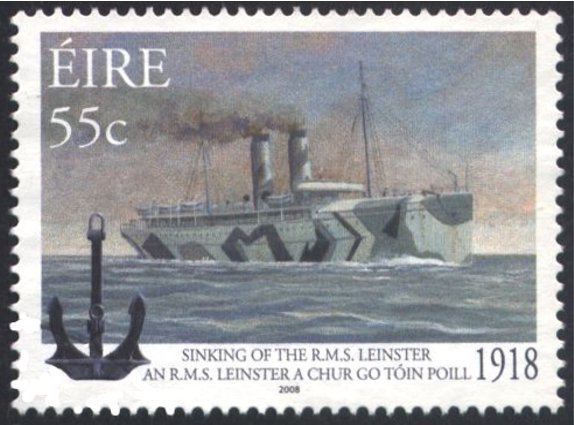

Many questioned were asked afterwards why the boat was not properly protected from attack by observation balloons overhead? That protection had been removed in the recent past, and thus the RMS Leinster was painted in camouflage (see the stamp above)

International Outrage: The sinking provoked widespread outrage in the Allied countries. From the US Irish tenor John McCormack, whose brother-in-law was lost, publicly condemned the sinking. From England Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scouts, sent a telegram of sympathy on the death of John Ross, secretary of the Howth Yacht Club, who was on his way to a scouting conference. But the most significant comments came from US President Woodrow Wilson on 14 October. Referring to German peace overtures made on 4 October, he said:

‘At the very time that the German government approaches the government of the United States with proposals of peace its submarines are engaged in sinking passenger ships at sea.’

With the ghost of the Leinster threatening the possibility of peace negotiations, Germany responded on 20 October, agreeing to cease hostilities against merchant ships. The attacks stopped the following day. An armistice was agreed and the war itself ended on 11 November 1918.

The RMS Leinster lies in 28m of water, 5 miles east of the Kish Lighthouse [see Diving the RMS Leinster] [ship survey 2015]

====

Denis’ Funeral and Last Resting Place

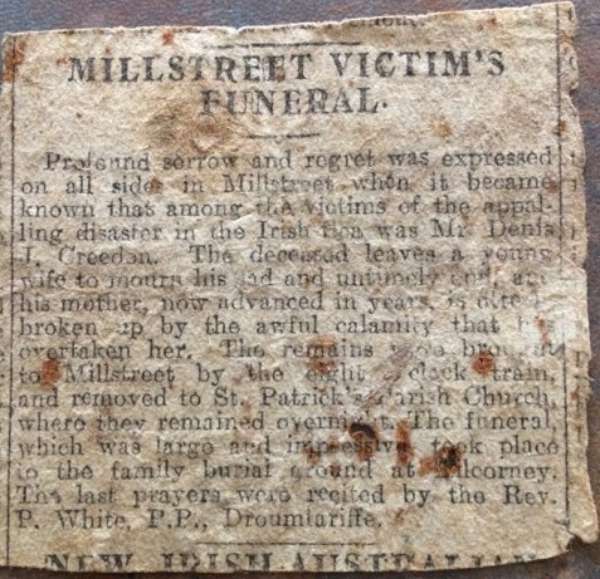

“MILLSTREET VICTIM’S FUNERAL: Profound sorrow and regret was expressed on all sides in Millstreet when it became known that among the victims of the apparelling disaster in the Irish sea was Mr Denis J. Creedon. The deceased leaves a young wife to mourn his sad and untimely end, and his mother, now advanced in years is utterly broken up by the awful calamity that has overtaken her. The remains were brought to Millstreet by the eight o’clock train and removed to St. Patrick’s Parish Church where they remained overnight. The funeral which was large and impressive took place at the family burial ground at Kilcorney. The last prayers were recited by the Rev P. White, P.P., Dromtariffe.” – Irish Examiner 17th October 1918.

“MILLSTREET VICTIM’S FUNERAL: Profound sorrow and regret was expressed on all sides in Millstreet when it became known that among the victims of the apparelling disaster in the Irish sea was Mr Denis J. Creedon. The deceased leaves a young wife to mourn his sad and untimely end, and his mother, now advanced in years is utterly broken up by the awful calamity that has overtaken her. The remains were brought to Millstreet by the eight o’clock train and removed to St. Patrick’s Parish Church where they remained overnight. The funeral which was large and impressive took place at the family burial ground at Kilcorney. The last prayers were recited by the Rev P. White, P.P., Dromtariffe.” – Irish Examiner 17th October 1918.

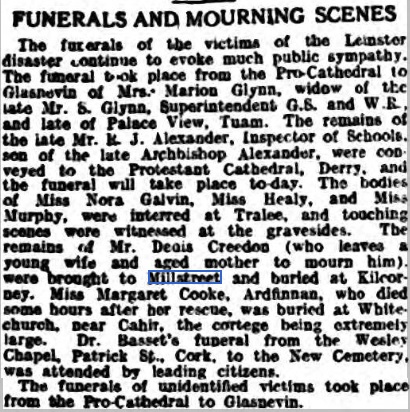

(Irish Independent 18 Oct 1918)

(Irish Independent 18 Oct 1918)

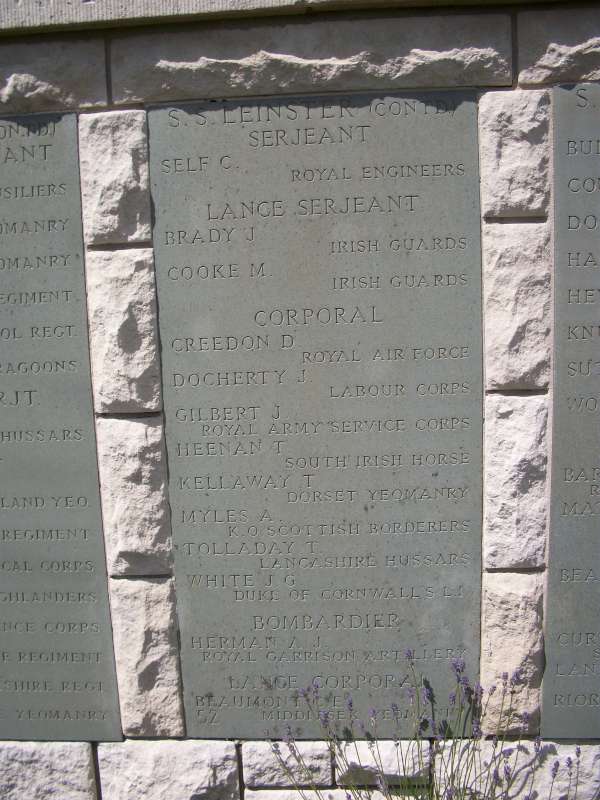

Corporal Denis Creedon, Royal Air Force – commemorated on panel 52 of the Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton [Commonwealth War Graves Commission] [Find a Grave]

Corporal Denis Creedon, Royal Air Force – commemorated on panel 52 of the Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton [Commonwealth War Graves Commission] [Find a Grave]

That Denis is commemorated at Hollybrook is unusual because Hollybrook Memorial is generally reserved for soldiers that have been lost at sea: “The Hollybrook Memorial commemorates by name almost 1,900 servicemen and women of the Commonwealth land and air forces* whose graves are not known, many of whom were lost in transports or other vessels torpedoed or mined in home waters (*Officers and men of the Commonwealth’s navies who have no grave but the sea are commemorated on memorials elsewhere). The memorial also bears the names of those who were lost or buried at sea, or who died at home but whose bodies could not be recovered for burial.” – History of Hollybrook Memorial

There is one other Millstreet man remembered at the Hollybrook Memorial (panel 31) – Patrick Carey, originally from Kilgarvan, he lived and worked here as a blacksmith, and married Margaret Moynihan of Mill Lane, with whom he had two children. He was returning to Dover injured from the front on the Hospital Ship Anglia in 1917, when it hit a mine and sank in fifteen minutes.

Grave Report for Cpl Dennis Creedon implies that his body was lost at sea [CWGC]

Grave Report for Cpl Dennis Creedon implies that his body was lost at sea [CWGC]

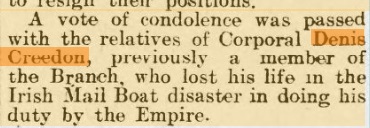

United Irish League: A vote of condolence was passed with the relatives of Corporal Denis Creedon, previously a member of the Branch, who lost his life in the Irish Mail Boat disaster in doing his duty by the Empire. [Aberdare Leader – 19th October 1918]

United Irish League: A vote of condolence was passed with the relatives of Corporal Denis Creedon, previously a member of the Branch, who lost his life in the Irish Mail Boat disaster in doing his duty by the Empire. [Aberdare Leader – 19th October 1918]

====

UBoat-123

In late 1918 the German army were being worn down by the relentless assaults of the Allied forces. The Germany fleet, still confined to port, was on the verge of mutiny. Meanwhile the men of the submarine service continued to attack enemy merchant shipping. In the final weeks of the war submarine UB-123 left Germany. On board were 35 young men who were determined to strike a blow at their country’s enemies. Commanded by twenty-seven year old Robert Ramm, UB-123 sailed north of Scotland and entered the Atlantic. Then sailing down Ireland’s west coast and along her south coast, the submarine turned north into the Irish Sea. There on 10 October 1918 she torpedoed and sunk the R.M.S. Leinster.

On 18 October 1918, while returning to Germany, UB-123 struck a mine in the North Sea. Robert Ramm and all of his young crew were lost.

Read: Why the R.M.S. Leinster was sunk: First World War U-boat campaign

====

Loose ends:

- We failed to find Denis in the 1911 census

- There’s a Denis Creedon from Macroom living a few miles from Mountain Ash where Denis and Julia got married. also working as a miner. a cousin perhaps?

- It’s interesting that Julia’s address is given as Laught in his service record. why?

Many thanks to Eileen and Mary for the help with researching the information above.